Unraveling a truly one-dimensional carbon solid

Researchers present a direct first proof of stable ultra-long 1D carbon chains, thus paving the way for the bulk production of carbyne

Even in its elemental form, the high bond versatility of carbon allows for many different well-known materials, including diamond and graphite. A single layer of graphite, termed graphene, can then be rolled or folded into carbon nanotubes or fullerenes, respectively. To date, Nobel prizes have been awarded for fundamental works on both graphene (2010) and fullerenes (1996). Although the existence of linear acetylenic carbon, an infinitely long carbon chain also called carbyne, was already proposed in 1885 by Adolf von Baeyer, who received a Nobel Prize for his overall contributions to organic chemistry in 1905, scientists have not yet been able to synthesize this material. Von Baeyer even suggested that carbyne would remain elusive, as its high reactivity would always lead to its immediate destruction. Nevertheless, carbon chains of increasing length have been successfully synthesized over the last 50 years.

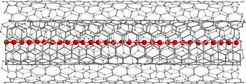

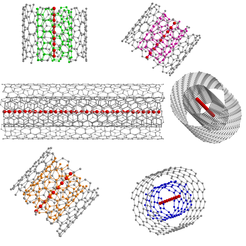

Schematic representations of confined ultra-long linear acetylenic carbon chains inside different double-walled carbon nanotubes

So far, the record has been a chain made of around 100 carbon atoms (2003). This record has now been broken by more than a factor 50 with the first-time demonstration of micrometer length-scale chains published in Nature Materials today. Researchers from the University of Vienna led by Thomas Pichler have developed a novel and simple approach to stabilize carbon chains with a record length of more than 6,400 carbon atoms. They use the confined space inside a double-walled carbon nanotube as a nanoreactor to grow ultra-long carbon chains on a bulk scale. In collaboration with the groups of Kazu Suenagas at the AIST in Japan, Lukas Novotny at the ETH Zürich and the theory group of Angel Rubio at the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter at CFEL in Hamburg and at the UPV/EHU in San Sebastián, the existence of the chains has been unambiguously confirmed by using a multitude of sophisticated, complementary methods. These are temperature-dependent near- and far-field Raman spectroscopy with different lasers (for the investigation of electronic and vibrational properties), high-resolution transmission electron spectroscopy (for the direct observation of carbyne inside the carbon nanotubes) and X-ray scattering (for the confirmation of bulk chain growth). “The direct experimental proof of confined ultra-long linear carbon chains, which are two orders of magnitude longer than the longest proven chains so far, can be seen as a promising step towards the final goal of unraveling the holy grail of truly 1D carbon allotropes, carbyne,” explains Lei Shi, first author of the paper.

Carbyne is very stable inside double-walled carbon nanotubes. This property is crucial for its eventual application in future materials and devices. According to theoretical models, carbyne’s mechanical properties exceed all known materials, outperforming both graphene and diamond (for instance, it is 40 times stiffer than diamond, twice as stiff as graphene and has a larger tensile strength than all other carbon materials). Carbyne’s electrical properties depend on the length of the one-dimensional chain, thus suggesting novel nanoelectronic applications in quantum spin transport and magnetic semiconductors in addition to its general appeal in physics and chemistry. “This work provided an example of a very efficient and fruitful collaboration between experiments and theory in order to unravel and control the electronic and mechanical properties of low-dimensional carbon-based materials. It led to the synthesis and characterization of the longest ever-made linear carbon chain. These findings provide the basic testbed for experimental studies concerning electron correlation and quantum dynamical phase transitions in confined geometries that were not possible before. Furthermore, the mechanical and electronic properties of carbyne are exceptional and open a wealth of new possibilities for the design of nanoelectronic as well as optomechanical devices,” concludes Angel Rubio.